Adding Undefeatable Protection to Any Process Using Virtual Machine Introspection

In my last post I talked about the current state of open source virtual machine introspection (VMI) and how I’d like to take a stab at bringing it back to life as best I can. In this post we’re going go over an example of just how powerful VMI can be as work towards cleaning up the IntroVirt repo and getting it into a better, more usable state, continues.

Since my post last week, a good amount of progress has been made. The original creator of IntroVirt (Steve!) is back on to help, quickly updating the KVM patch for a much newer Linux kernel (6.18) as well as getting started with testing on Windows 11 (which turns out to kind-of work). We should be seeing a push or PR for those changes shortly.

While he’s been doing that, I’ve been working on some cleanup, testing, bug fixes, automation, and patch improvements. libmspdb has a new version with some cleanup, and bug fixes as well as automated builds, testing, and releases using GitHub actions. kvm-introvirt has a bunch of fixes to the patch, some cleanup, automation in GitHub actions and support for 2 Proxmox (PVE) kernels. We also have a discord now and a roadmap!! It’s been a busy couple of weeks.

Finishing The VMCALL Example

As I was going through, cleaning things up, and planning out next steps, I noticed an examples directory in the IntroVirt repository with 2 example. One practically blank, and the other 99% complete. So naturally, we delete the blank one as if it never existed, and finish the other one: vmcall_interface.cc. I don’t want to just finish it and move on though, I want to make it cooler.

What is the point of vmcall_interface.cc? It’s probably best to understand it first. The vmcall_interface.cc example demonstrates how to create an IntroVirt tool that can receive commands from processes in the guest to perform actions on behalf of those processes that wouldn’t normally be possible without VMI. For example, you could make a command to elevate an unprivileged guest process to admin while completely bypassing all security controls. Or you could give guest processes a way to request additional protection from the hypervisor: preventing termination, or debugging. We’re going to go with the later for this example.

The fundamental thing at play here is the vmcall instruction. It’s a regular old assembly instruction like any other, but when it runs, it triggers a VM exit and then the hypervisor decides what to do. Hyper-V has them, KVM has them, Xen has them too, they all have them. What makes this so powerful is that we can write a tool that enables custom handling of vmcall instructions that work at any privilege level without recompiling or modifying the hypervisor (since the kvm patch for IntroVirt exposes that functionality already).

Let’s start with the in-guest component. We just need a simple user-mode application in C with an assembly stub to perform the vmcall instruction. Here’s a simple assembly stub that implements 2 capabilities (the one on GitHub has way more comments and features):

.code

; Reverse a NULL-terminated string

HypercallReverseCString PROC

mov rax, 0FACEh

mov rdx, rcx

mov rcx, 0F000h

vmcall

ret

HypercallReverseCString ENDP

; Protect a process from termination, debug, and modification

HypercallProtectProcess PROC

mov rax, 0FACEh

mov rcx, 0F002h

vmcall

ret

HypercallProtectProcess ENDP

Then we can use it with a little C program:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <windows.h>

extern uint64_t HypercallReverseCString(char *c_str);

extern uint64_t HypercallProtectProcess();

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

uint64_t status = 0;

char test_str[] = "Hello, IntroVirt!";

printf("Original string: %s\n", test_str);

status = HypercallReverseCString(test_str);

if (status == 0) {

printf("Reversed string: %s\n", test_str);

} else {

printf("Failed. Status code: %llu\n", status);

}

status = HypercallProtectProcess();

if (status == 0) {

while (1) {

printf("This process is protected\n");

Sleep(2000);

}

} else {

printf("Failed. Status code: %llu\n", status);

}

return 0;

}So now let’s explain what’s happening here. In our vmcall_interface tool we expose “service codes”. These are the “things” we can do and they map directly to the two assembly functions from above. We can reverse a null-terminated C-string and protect the calling process from debugging, termination, or injection. The service codes are defined in vmcall_interface.cc like this:

enum IVServiceCode { CSTRING_REVERSE = 0xF000, PROTECT_PROCESS = 0xF002 };We can make as many service codes as we want, and we can implement them however we want. For this simple example we just use an enum to define our codes as arbitrary values. It is the responsibility of the in-guest process to execute the vmcall instruction with the appropriate service codes.

The complete version of vmcall_interface will have more service codes and the in-guest components may be more complicated. These snippets simply illustrate the core of what’s going on. Any additional service codes or functionality is just more of the same with tweaks to perform different actions or add additional protections.

To make a vmcall we simply need to get the vmcall instruction to run. That’s what our assembly stub is for. Then we need to pass in our service code and any other arguments in appropriate CPU registers. So, if that’s all, how does IntroVirt know about our vmcall? Well, there’s one more piece. We need to set a register to a special constant value that let’s IntroVirt know this vmcall is an event that should be sent to an IntroVirt tool instead of the default logic of the KVM hypervisor. We can see a simplified version of this logic in the kvm-introvirt KVM patch:

int kvm_emulate_hypercall(struct kvm_vcpu *vcpu)

{

unsigned long nr, a0, a1, a2, a3, ret;

int op_64_bit;

nr = kvm_rax_read(vcpu);

if(nr == 0xFACE) {

const uint64_t original_rip = kvm_rip_read(vcpu);

if (vcpu->vmcall_hook_enabled) {

kvm_deliver_vmcall_event(vcpu);

}

++vcpu->stat.hypercalls;

if (original_rip == kvm_rip_read(vcpu)) {

return kvm_skip_emulated_instruction(vcpu);

}

return 0;

}

//...the rest of kvm_emulate_hypercall() is just the normal

// non-introvirt code for handling hypercalls in KVM.So we can see here, if we ensure the RAX register is set to 0xFACE when we make our vmcall then the handling will divert away from stock KVM into IntroVirt. In addition to the 0xFACE value we also need to pass in the service code and any arguments for the service we’re implementing. To reverse a C-String, we just need the service code and the pointer to the string. For the process protection we just need the service code. If we look at vmcall_interface.cc we can see the service code is expected to be in the RCX register.

switch (regs.rcx()) {

case CSTRING_REVERSE:

return_code = service_string_reverse(event);

break;

case PROTECT_PROCESS:

return_code = service_protect_process(event);

break;

}and for the service_string_reverse we expect the pointer to the string to be in the RDX register. And with that, we now have enough information to actually understand the assembly stub from earlier:

.code

; Reverse a NULL-terminated string

HypercallReverseCString PROC

mov rax, 0FACEh

mov rdx, rcx

mov rcx, 0F000h

vmcall

ret

HypercallReverseCString ENDP

; Protect a process from termination, debug, and modification

HypercallProtectProcess PROC

mov rax, 0FACEh

mov rcx, 0F002h

vmcall

ret

HypercallProtectProcess ENDPIn both cases we put 0xFACE (0FACEh in this assembly syntax) in the RAX register. Then we put the service codes 0xF000 and 0xF002 in RCX. The only catch is in HypercallReverseCString where we do mov rdx, rcx. This requires some understanding of calling conventions in Windows, but to skip the full explanation, when we call HypercallReverseCString(test_str), the address of test_str ends up in RCX, and since we actually need that to be in RDX and the service code to be in RCX, we do a quick switch to re-arrange things so it’s all prepped for the vmcall.

As we’ve seen up to this point, when the hypervisor sees these vmcall instructions with those values in those registers, and event will be sent to any running IntroVirt tools attached to that guest VM. In this case, it will be our vmcall_interface tool which will parse the service code in the switch, case above and call one of service_string_reverse or service_protect_process, both of which are fairly straightforward:

int service_string_reverse(Event& event) {

auto& vcpu = event.vcpu();

auto& regs = vcpu.registers();

try {

// RDX has a pointer to the string to reverse

guest_ptr<void> pStr(event.vcpu(), regs.rdx());

// Map it and reverse it

guest_ptr<char[]> str = map_guest_cstring(pStr);

reverse(str.begin(), str.end());

} catch (VirtualAddressNotPresentException& ex) {

cout << ex;

return -1;

}

cout << '\t' << "String reversed successfully\n";

return 0;

}

int service_protect_process(Event& event) {

auto& task = event.task();

lock_guard lock(mtx_);

protected_pids_.insert(task.pid());

return 0;

}The service_reverse_string function is the simplest example since it runs and completes everything it needs to do right there and when it returns the string is reversed.

The service_protect_process is harder to show in one snippet since it involves tracking the process and then monitoring system calls. In the snippet above we add the PID to our protected_pids_ variable. Then we need to handle the NtOpenProcess system call:

case SystemCallIndex::NtOpenProcess: {

auto* handler = static_cast<nt::NtOpenProcess*>(wevent.syscall().handler());

auto desired_access = handler->DesiredAccess();

auto* client_id = handler->ClientId();

const uint64_t target_pid = client_id->UniqueProcess();

lock_guard lock(mtx_);

if (protected_pids_.count(target_pid)) {

if (desired_access.has(nt::PROCESS_TERMINATE) ||

desired_access.has(nt::PROCESS_VM_WRITE) ||

desired_access.has(nt::PROCESS_VM_OPERATION) ||

desired_access.has(nt::PROCESS_CREATE_THREAD) ||

desired_access.has(nt::PROCESS_CREATE_PROCESS) ||

desired_access.has(nt::PROCESS_SET_INFORMATION))

{

handler->ClientIdPtr(guest_ptr<void>());

}

}

break;

}NtOpenProcess is the precursor to basically anything that can be done to a process. It’s not possible to debug a process, read its memory, write its memory, terminate it, inject into it, or anything without first opening a handle to it. So this snippet shows that all we need to do is look for processes opening our protected process, check the access rights they are requesting, and if we don’t like it, simply change the ClientId paramter to a NULL pointer, which will result in an invalid parameter at the kernel level and the call will fail. Once that’s handled, we just have a snippet for catching terminate and we’re basically done:

case SystemCallIndex::NtTerminateProcess: {

auto* handler = static_cast<nt::NtTerminateProcess*>(wevent.syscall().handler());

if (!handler->will_return() || handler->target_pid() == wevent.task().pid()) {

lock_guard lock(mtx_);

protected_pids_.erase(wevent.task().pid())

break;

} else {

lock_guard lock(mtx_);

if (protected_pids_.count(handler->target_pid()) != 0) {

// This process is protected. Deny termination

handler->ProcessHandle(0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF);

break;

}

}

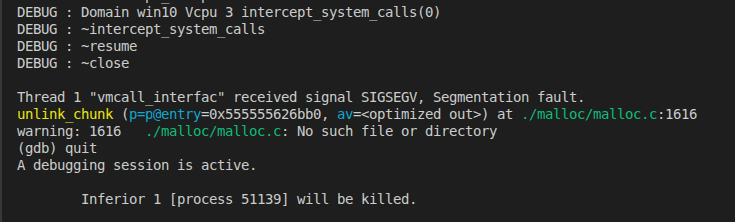

}This way the process can still exit on it’s own but any other process trying to terminate it will fail. We achieve this by intercepting the NtTerminateProcess call and setting the process handle to an invalid handle value which will cause the call to fail. We check for self-terminate by checking for NtTerminateProcess calls that won’t return or who’s PID match the target process. Let’s see it in action:

The process can run and exit on its own, but trying to kill it in task manager fails. And, something unexpected happened while I was recording, it looks like MsMpEng.exe attempted to open the process and we blocked it. That’s kind-of funny since that’s Microsoft’s malware protection service. We really do have a lot of power to do whatever we want from the hypervisor.

About Me

Sean LaPlante

Software Engineer

Hello

Follow Me

Connect with me if you want.

Leave a Reply